By Costas Paris in London, Robbie Whelan in New York and Kejal Vyas in Bogotá, Colombia

The giant Panama Canal expansion opens June 26 amid much fanfare and one of the worst shipping industry slumps ever. While it won’t do anything to help the dire state of the industry near-term, the changes are critical to Western trade in the long run.

The canal, which handles about a third of Asia-to-Americas trade, had no choice but to expand. As the industry copes with its downturn, major shipping companies are pooling their resources and using fewer but much bigger ships—ones that are too large to fit through the pre-expansion Panama Canal.

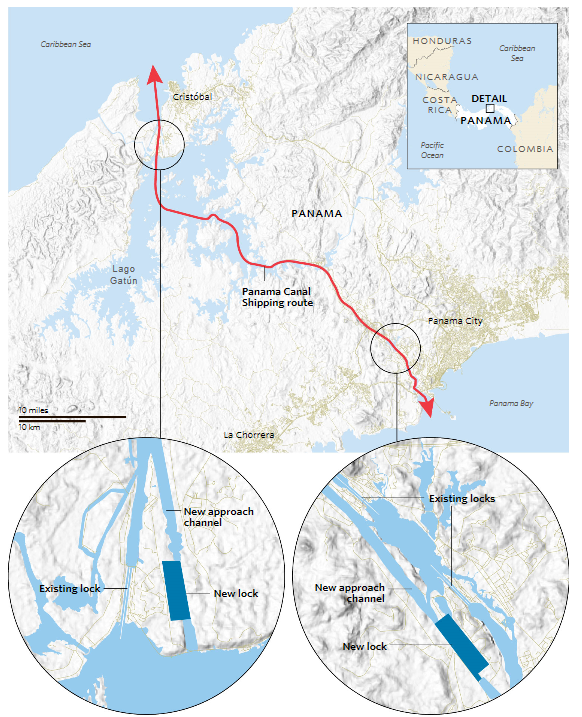

The Panama Canal can now accommodate vessels that are longer, wider and heavier than before, thanks to an expansion that was nine years in the making. The face-lift was crucial to compete in a world where ships are getting bigger and bigger. Illustration: Heather Seidel for The Wall Street Journal

The nine-year, $5.4 billion expansion more than doubles the canal’s cargo capacity. A third lane has been added to the canal that accommodates ships large enough to carry up to 14,000 containers, compared with around 5,000 currently. This alleviates a cargo bottleneck caused by the smaller ships that was due to get worse over time.

The expansion makes the Panama Canal more competitive with the Suez Canal in Egypt, shortening the one-way journey by sea from Asia to the U.S. East Coast by roughly five days and eliminating the need for a trip around Cape Horn to get to the Atlantic.

And while some East Coast ports—Baltimore, Miami and Norfolk, Va.—are ready to accommodate much bigger ships, others aren’t, according to Paul Bingham, a port economist with EDR Group Inc. Dredging projects are still under way at the ports of Savannah, Ga., and Charleston, S.C., and the tidal channel on the Savannah River has only received approval to be deepened to 47 feet—not the 50 feet required for the canal’s largest ships.

Sources: Panama Canal; OpenStreetMap

Some of the ports lack infrastructure such as cranes and docking space to handle the ships. At the port of New York and New Jersey, the three largest terminals are walled off to the largest container ships by the Bayonne Bridge, which the local port authority is raising by more than 60 feet at a cost of more than $1.3 billion.

Though ship transits through the Panama Canal rose 3.7% last year compared with a rise of less than 1% the year before, the increase in cargo volumes slowed to less than 1% from about 7% the prior year.

Expansion was a must if the Panama Canal was to continue to play its key role in global trade. In the shipping industry, supply exceeds demand by about 30% and freight rates barely cover fuel costs. In the move to bigger and more efficient ships, many of the smaller ships that were tailor-made for the Panama Canal are expected to soon become obsolete. The Panama Canal had to expand to continue to expedite trade to the U.S. East Coast, to lessen cost for shippers and, over time, take pressure off West Coast ports.

Some 6% of global trade in terms of capacity, or 340 million tons of goods, passed through the canal last year. Still, it has lost 10% to 15% of annual revenue to the Suez Canal over the past three years, according to canal executives. To complete the expansion, Panama Canal operators procured $2.3 billion from lenders in Japan, Europe and the Americas.

The bigger ships are expected to move through the canal substantially more refrigerated cargo from South America, like fresh produce, fish and meat, to East Coast ports, according to Basil Karatzas, of New York-based Karatzas Maritime Advisors & Co.

The first trial run with a Post-Panamax cargo ship in the new sets of locks on the Atlantic side of the Panama Canal, on June 9, 2016. Photo: carlos jasso/Reuters

They are also poised to capitalize on the surge in U.S. natural-gas output and the interest in new export markets including Japan, South Korea, India and China. By 2020, Mr. Bazán said he expects liquid natural gas to be one of the main products transported through the canal.As of now, only one facility— Cheniere Energy Inc. ’s Sabine Pass terminal, in Cameron Parish, La.—is capable of processing natural gas for export from the Gulf of Mexico.

“What the Panama Canal does more than anything is it contributes to the LNG market becoming more of a global market,” said Octavio Simões, president of Sempra LNG & Midstream, a unit of Sempra Energy.

The expansion won’t solve all of the Panama Canal’s challenges. The canal still won’t be able to handle the very biggest container ships, which move up to 20,000 containers.

The expansion’s launch date was delayed by two years because of cost overruns, leaky locks and labor disputes, in contrast to the Suez Canal, where work for a new channel was completed on time and in only 12 months.Earlier this month the Suez Canal cut its tolls by up to 65% for certain trades—including routes from Asia to the U.S. East Coast. “It’s a price action directly aimed at competing more effectively with the expanded Panama Canal,” said Lars Jensen, CEO of Copenhagen-based SeaIntelligence Consulting.

Comments are closed