The stagnation of global trade has pushed South Korea’s shipbuilders close to breaking point

By KWANWOO JUN and IN-SOO NAM

Updated Nov. 1, 2016 1:29 a.m. ET

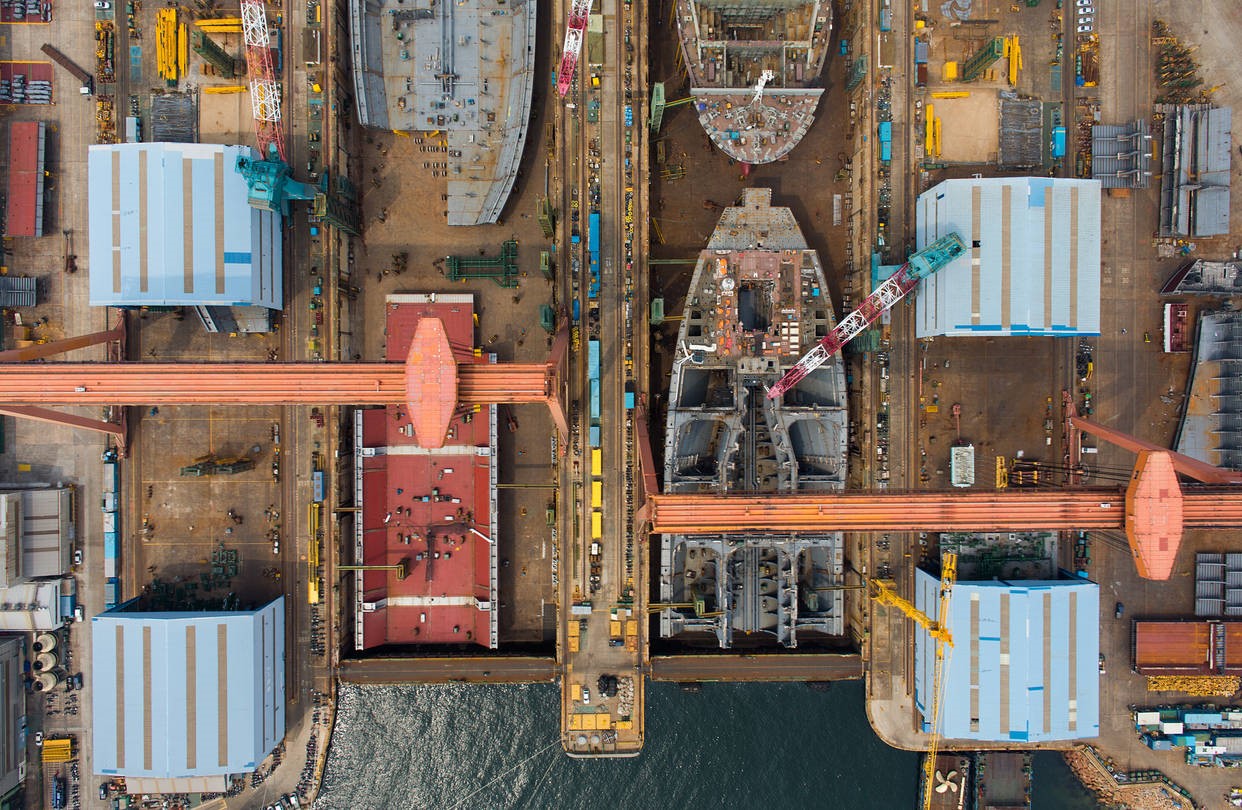

Ships stand under construction in this aerial photograph taken above the Hyundai Heavy Industries Co. shipyard in Ulsan, South Korea, in 2015. PHOTO: BLOOMBERG NEWS

SEOUL—South Korea plans to spend $9.6 billion on ships from local yards to stave off the collapse of its shipbuilding industry, the latest evidence of the wrenching impact of a prolonged slump in global trade.

For decades, shipbuilding has been a driving force of the South Korean economy. The country is home to the world’s three biggest shipbuilders measured by order volume, and last year ships accounted for 7.6% of South Korea’s exports.

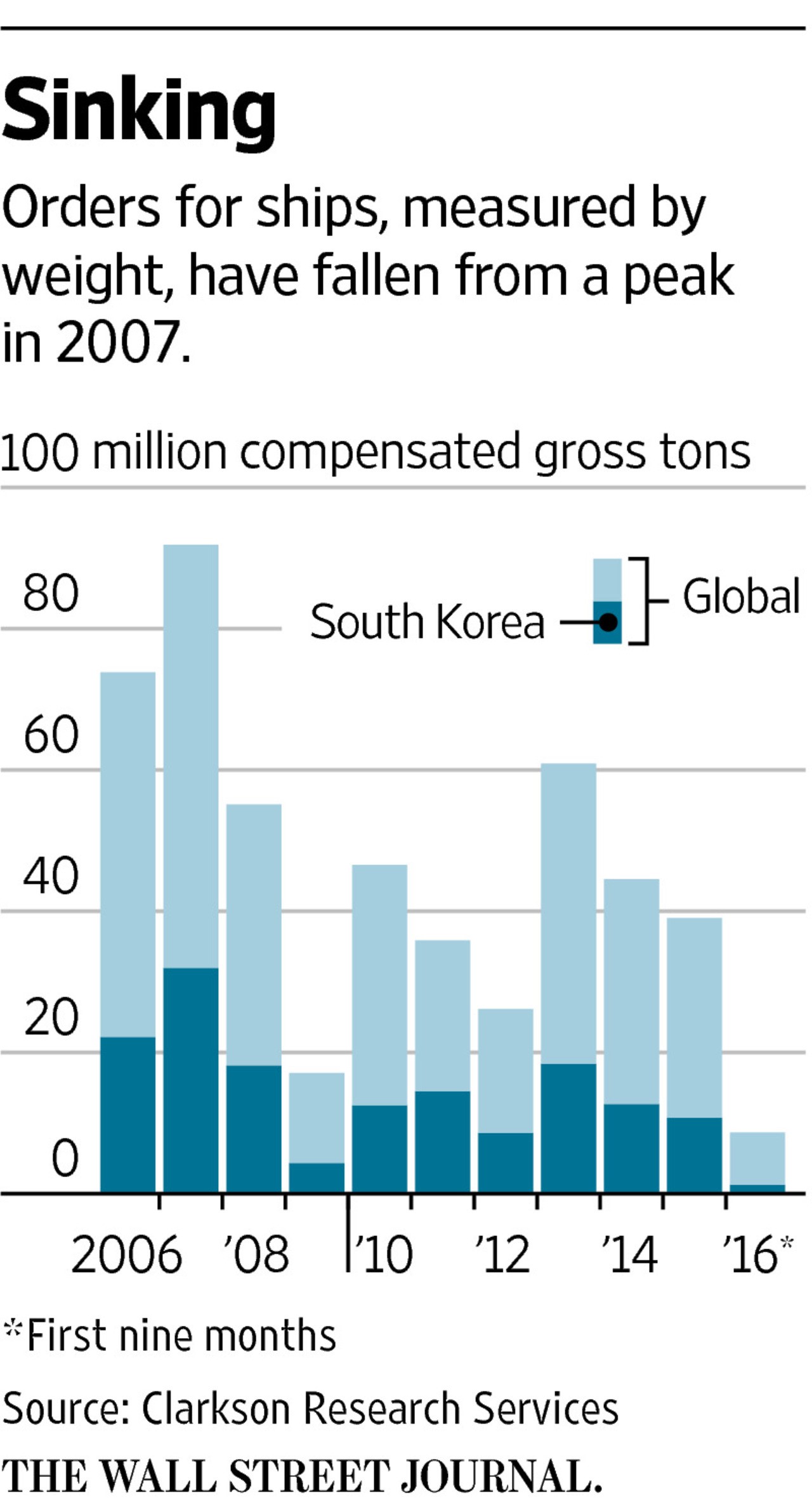

But a steep slide in orders has weighed heavily on the industry after the 2008 global economic crisis pummeled demand from shipping companies and lower-cost Chinese shipbuilders began to eat into South Korean companies’ business. The recent stagnation of global trade has pushed the companies close to the breaking point.

New vessel orders won by South Korean shipbuilders in the past nine months of this year were down 87% from the year-earlier period, according to the trade ministry.

All the major South Korean shipyards, including the big three— Hyundai Heavy Industries Co., Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering Co. and Samsung Heavy Industries Co.—have sold noncore assets and shed staff under bank-led restructuring plans.

Consulting firm McKinsey & Co. said earlier this month that Daewoo is unlikely to survive past 2020 if the market downturn continues. Daewoo said the report was exaggerated.

A glut of container ships in the water and not enough cargo to fill them in the past few years has led to record-low freight rates, hammering the industry and prompting owners to further cut or push back new ship orders.

On Monday, Japan’s three largest shipping companies by revenue said they would merge their container-shipping operations to cope with the global decline in the business.

South Korean Finance Minister Yoo Il-ho said Monday the government would help the shipbuilding companies cope with an “order cliff” by directly ordering or providing financing for more than 250 vessels—valued at roughly 11 trillion won ($9.6 billion)—through 2020.

About half will be boats for small shipping companies and the fishing industry. The remainder will be for government use, such as coast-guard vessels and warships, as well as ferries and patrol boats.

It is unclear whether the plan will help the companies survive.

Officials at some of the major shipbuilders said the plan fell short of expectations because orders are mainly targeted at smaller shipyards. “It doesn’t address the trough in orders for large and profitable vessels such as container ships and tankers,” said a shipyard official.

A group of opposition lawmakers denounced the plan for attempting to pass “a ticking bomb” to future administrations.

But shipbuilding analyst Yu Jae-hun at Seoul-based NH Investment & Securities said the plan will carry shipyards through to a pickup in global orders from 2018 based on his analysis of business cycles.

The decision to pump billions of dollars of public money into shipbuilders reflects their significant role in South Korea’s economy and as employers. The sector accounted for 7.1% of the country’s total manufacturing jobs last year, according to the government.

South Korean state and commercial banks have already injected billions of dollars into some beleaguered shipbuilders that are deemed too big to fail. In June, the government and the central bank set up an 11 trillion won fund to recapitalize state-run banks so they can absorb bad debts from ailing shipping and shipbuilding companies.

Vice Trade Minister Jeong Marn-ki said Monday the government hopes to keep the “big three” shipbuilders for now, although it will ask them to take more stringent restructuring measures, including deep job cuts and further sales of noncore businesses.

The country’s three biggest shipbuilders will have to cut 32% of their total workforce by 2018 and reduce their operations by 23%, the government said.

The deck of a container ship at the Daewoo DSME shipyard in Okpo, south of Busan, in a 2014 file photo. PHOTO:AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE/GETTY IMAGES

The finance ministry also said the government would offer 6.5 trillion won in financing for local shipping companies to acquire new bigger vessels, which help profit margins. In addition, South Korea intends to create a state-backed ship-financing company with initial capital of one trillion won.

Slowing global trade and overcapacity have also battered shipping lines, with some companies forced to sell vessels at a discount or fold.

Hanjin Shipping Co., South Korea’s biggest container operator, filed for bankruptcy in late August and is under court order to dispose of assets such as ships and terminals.

Hyundai Merchant Marine Co., Hanjin’s South Korean rival, was saved from going bankrupt in July after a rigorous creditor-led debt overhaul.

Write to Kwanwoo Jun at [email protected] and In-Soo Nam at [email protected]

Comments are closed